…So much, in fact, that he apparently lifted passages verbatim from my performance art manifesto for his recent “performance art plagiarism” on Twitter.

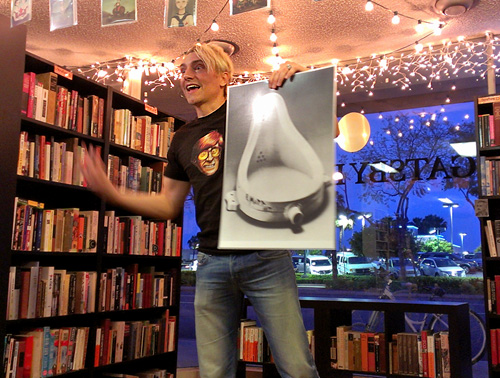

If this whole drama is news to you, it really started in late 2013 when the world learned LaBeouf had plagiarized word-for-word from Justin M. Damiano, a comic by Daniel Clowes, for LaBeouf’s short film Howard Cantour. Caught red-handed, but determined to laugh off his asininity, LaBeouf presented a mea culpa through plagiarized apologies on Twitter, then did a little skywriting, and then offered the excuse that this had all been “metamodernist performance art” — that, oh you know, his charmed life is really just a performance art piece — all of which climaxed with a final twittering of performance art aphorisms that read almost like a performance art manifesto. An astute tipster googled some of LaBeouf’s tweets, and lo, discovered they’d been lifted straight from the performance art manifesto on my web site, as well as from writings of performance artist Marina Abramovic and others.

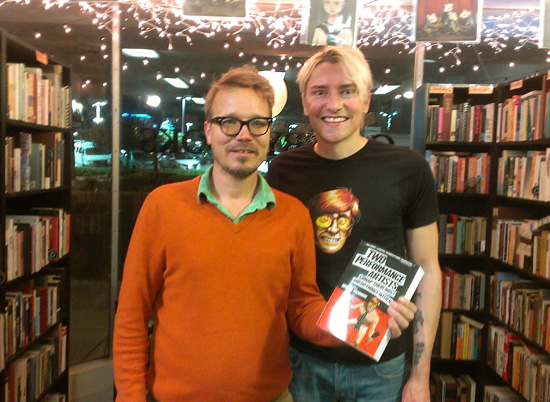

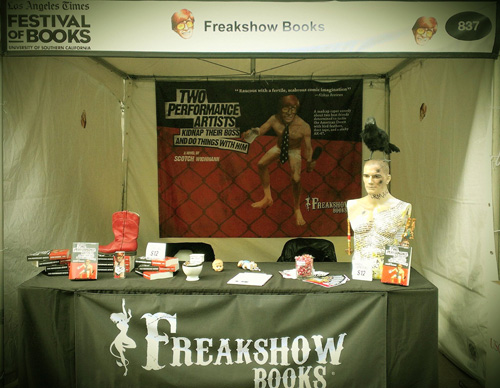

You can check out his (un)original tweets, my manifesto (originally published in 2009 as evidenced by Archive.org), or compare them side-by-side. As payment for my writerly services, I won’t object if Shia wants to buy a few thousand copies of my novel when it comes out April 10th. I’ll even sign each one (unless, of course, he’d prefer to sign my signature himself? Ha).

I’ve received buckets of sympathy from supporters & cohorts, which I truly appreciate. Sincerely: thank you for having my back.

But I need to say for myself: I’m not without a sense of humor, nor do I lack appreciation for pastiche, sampling, intertextual play, remaking, invoking past influences, and the like; these are how humans push ideas forward.

I was reminded today (thanks, Mark Axelrod) that French-American writer Raymond Federman termed this kind of textual borrowing “playgiarism” to distinguish it from less artful, more insidious brands of thievery:

“To answer the question once and for all. I cannot explain how Playgiarism works. You do it or you don’t. You’re born a Playgiarizer or you’re not. It’s as simple as that. The laws of Playgiarism are unwritten. Like incest, it’s a taboo. It cannot be authenticated. The great Playgiarizers of all time — Homer, Shakespeare, Rabelais, Diderot, Rimbaud, Lautréamont, Proust, Beckett, Federman — have never pretended to do anything else. Inferior writers deny that they playgiarize because they confuse Plagiarism with Playgiarism. It’s not the same. The difference is enormous, but no one has yet been able to explain it. Playgiarism cannot be measured in weight or size. It is as elusive as what it playgiarizes.

Plagiarism is sad. It whines. It cries. It feels sorry for itself. It apologizes. It feels guilty. It hides behind itself.

Playgiarism on the contrary laughs all the time. It exposes itself. It is proud. It makes fun of what it does while doing it. It denounces itself.

That does not mean that Playgiarism is self-reflexive. How could it be? How can something reflect itself when that itself has, so to speak, no itself, but only a borrowed self. A displaced self.

If this is getting too complicated, too intellectual, too abstract, then let me put it in simpler terms — on the Walt Disney mental level: Playgiarism is above all a game whose only rule is the game itself. The French would call that plajeu.”

Lit critic Larry McCaffery writes about 3 kinds of plagiarist hoaxes: the kind intended to remain undiscovered (e.g., forged painting), the kind intended to be detected (via irony or exaggeration), and the third: an exact forgery, but whose “forged nature is built into the project” in the form of a constructed context (the context allows for the forgery to be inferred).

With his list of “playgiarizing” authors above, Federman seems to cover all 3 kinds of hoaxery — plain thievery, artful dodgery, and structuralized disclosure, respectively — but I find these forms of plagiarism to be vastly different from each other on the ethical scale (and on this, Federman is suspiciously quiet). Since le jeu (“the game”) can’t be self-reflexive — it can’t confess, having no self — and in the case where the audience has no idea a game is even being played — the playgiarizing “borrower” is really playing the game alone, and for his or her own gain, at the expense of the author who did all the work.

My guess is that Shia intended to succeed, through hubris or ignorance, in the first kind of hoax with his film’s brazen theft of Daniel Clowes’s comic. After that embarrassing & expensive failure, he stumbled upon the third kind of hoax through trial and error, creating a “constructed context” by accident, insofar as his listless celebrity aura, stuttering initial apologies, and reputation as a goof quickly made it unbelievable that he’d authored any of the tweets — his ham-handedness became the context in which we no longer believed his claims of authorship. And thus, his tweetfest devolved into dorky, eye-rolling postmodern pastiche — what Fredric Jameson called the “emergence of a new kind of flatness or depthlessness, a new kind of superficiality in the most literal sense” — which was ironically (and accidentally) fitting for a celeb — and especially one trying to confidently bullshit his way forward in spite of total inexperience.

In short, I guess I take issue less with going uncredited as part of an art project, and more with being part of a failed “artist’s” blind grasp at justification for his own initial ethical failure. It just feels kind of icky.

From Federman’s “Story of the Sparrow”:

“The moral of this story: Your enemy is not necessarily the one who shits on your head. Your friend, however, is not necessarily the one who pulls you out of the shit. And besides, one should never twitter when one is buried in shit.”

With his willingness to clumsily screw artists everywhere, it’s no wonder “Shia LaBeouf” is an anagram for “I Has Oaf Lube.”

See? I has a sense of humor.